More alarm has been caused by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) actions today than by the abrupt 50 basis point raise by the US Federal Reserve. China’s predicament is one of increased unpredictability and underlying instability, in contrast to the Fed’s predictable judgements. At first look, the deflation, deleveraging, and economic slowdown all seem manageable; nevertheless, when combined with China’s recent policy changes, they present a concerning picture.

Post-Pandemic Struggles: The Slow Motion Slowdown

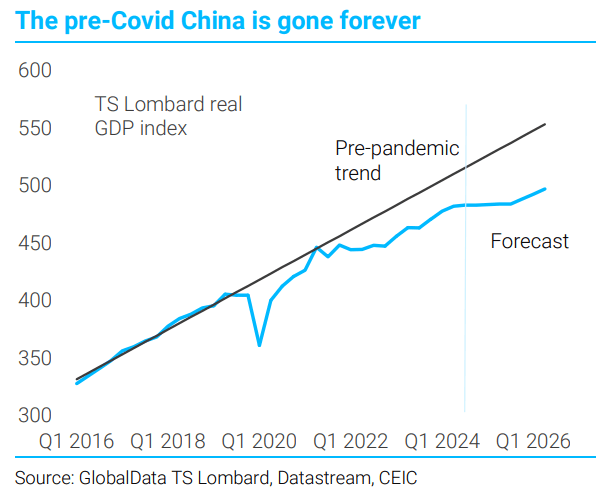

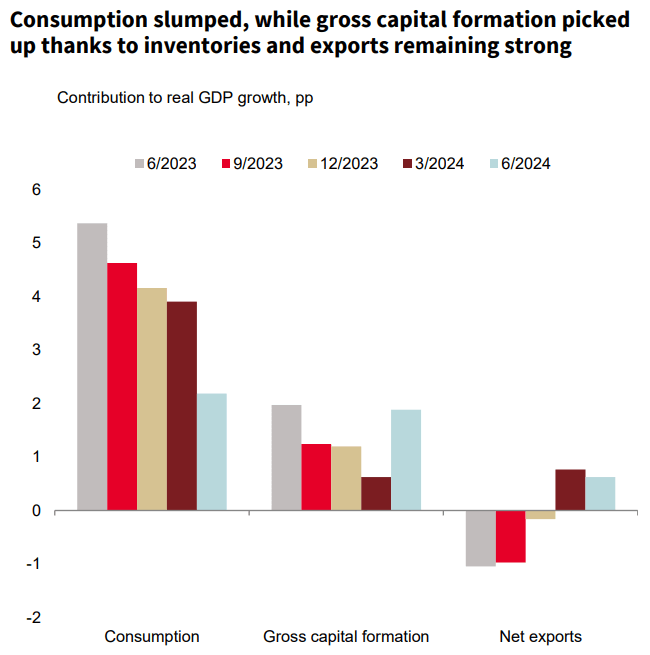

Following the pandemic, the Chinese economy is in a difficult situation. Consumption is still low, and the formerly robust real estate market is beginning to crumble. However, these problems have been partially concealed by the aggressive export of excess manufacturing capacity. Through its financing vehicles (LGFVs), the property industry, which is essential to local governments, is also experiencing difficulties, which further reduces government revenue.

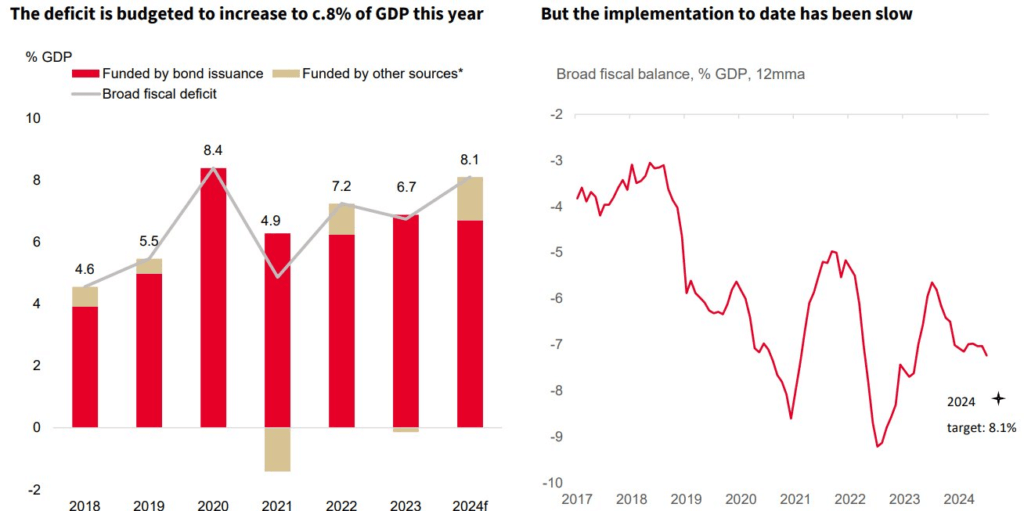

China has relied on a growing fiscal deficit to offset these challenges. However, this hasn’t had much of an impact on consumer spending, suggesting that fiscal stimulus might not be sufficient on its own to pull China out of this mess. Deeper issues are at play, as China’s historical dependence on exports and fixed asset investment (FAI) is coming under increasing pressure, particularly from the worsening post-pandemic lower consumption growth.

Unbelievably Low Nominal Growth and Deflation in the GDP

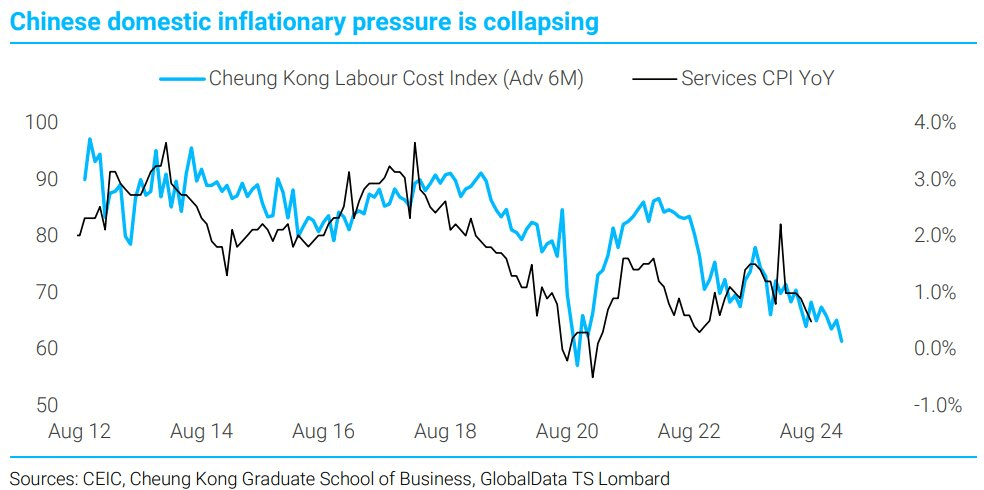

China’s GDP numbers may not appear alarming at first glance, but nominal GDP growth indicates otherwise. While real GDP growth is still increasing—albeit slowly—at a rate of about 4%, deflation is eroding these advances. This indicates that, despite China’s lower real GDP estimates, the country’s nominal GDP growth is falling even behind that of the US.

Strong exports are still primarily the result of poor imports, which indicate a decline in domestic demand. This covers up the economy’s inherent instability. Deflation is pinching already vulnerable industries like real estate in addition to reducing nominal growth.

Deposits and Property: A Difficult Feedback Cycle

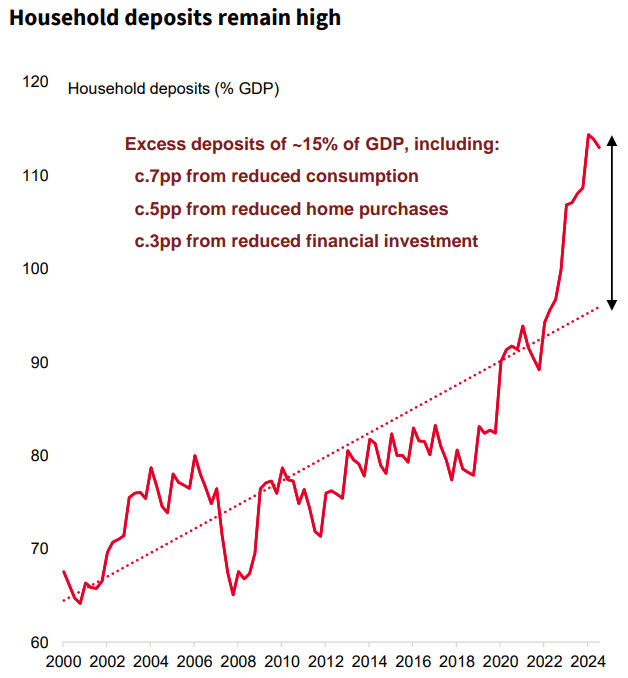

Household savings have increased as a result of lower consumption rates, and these funds are now going into banks rather than real estate or stock markets. The primary market in China continues to underperform the country’s real estate market. The slowdown is being exacerbated by falling property prices due to rising inventories.

Calling this a full-fledged crisis, though, might still be too soon. No significant bank or household loan defaults have occurred thus far, and the government is closely monitoring the situation. Yet there’s no denying the real estate industry’s massive growth drag.

Central Government Debt: Managing, Not Growing

The second significant issue is the way China’s central government is managing the country’s growing debt crisis. Up to now, the central government’s debt has been increased; but, in contrast to the United States, this has not resulted in increased nominal GDP growth. Rather, the majority of its use is in the management of debt restructuring, especially in the construction industry, where declining activity is depressing the economy as a whole.

Although the budget deficit is increasing, the economy is not being stimulated as it may be in other nations. Fiscal infusions are only plugging gaps rather than generating fresh growth because other sectors of the economy, such as real estate, are still struggling with growth. The economy is being further slowed down by the debt, which is being used to support underperforming assets.

Western Markets: Less Concerned for Now

The effects on Western markets are not as severe or immediate, despite the frightening nature of these developments. Most of China’s issues—particularly in property and related debts—are managed within its borders. However, there comes a larger price: slower growth and deflation, both of which may begin to reverberate through the world economy, especially the commodities markets.

In China, market dynamics are becoming less significant as the central government gains more control over capital. In response to the poor returns in real estate and financial sectors, households are saving more money and avoiding investments. Instead of promoting economic activity, this is causing more capital to remain in deposits.

Commodity Markets: The Flashing Warning Signs

Right now, commodities are the external markets’ top worry. The need for raw materials in China is decreasing, and it is more difficult to penetrate export markets. Production is still high, but profitability is low. The steel industry, which is frequently a good indicator of the state of the industry, is having trouble with falling prices and weak input prices going forward. These are warning indicators that demand is about to slow down more broadly.

A Slow Decay, Not a Crash

The most concerning aspect of China’s current economic situation is that it is not a dramatic collapse, unlike in 2015, when China’s unrest caused the world markets to plummet. Rather, this is a steady decline, an increasingly difficult to reverse downward spiral.

China may not be in imminent danger of collapsing catastrophically, but its economic problems are making things more difficult by slowing development. The country’s officials are navigating unfamiliar waters as debt, deflation, and growth combine to create a complicated dilemma that could take years to resolve.