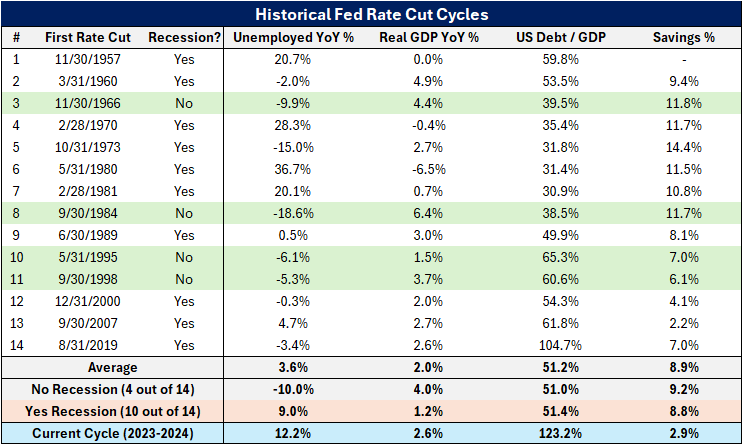

Recessions have preceded ten of the last fourteen rounds of rate cuts by the Federal Reserve. There have only been four exceptions: 1966, 1984, 1995, and 1998. These were times of exceptionally excellent economic conditions, unlike anything seen today, with lower debt levels, faster GDP growth, higher savings rates, and declining unemployment rates.

Although it is hard to forecast the economy with absolute confidence, historical evidence shows that rate reduction by the Federal Reserve are frequently a leading indicator of downturns in the economy. This pattern makes sense because the Federal Reserve often reduces rates in reaction to new developments in the economy.

The increase in unemployment is a major worry at the moment. The number of unemployed Americans increased by 12% from the previous year to 7.1 million by August 2024. Based on historical trends, double-digit rises in unemployment typically indicate additional increases, as the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) shows.

Currently, the unemployment rate has increased by 12.2% annually. The current economic climate is very different from the four historical “soft landing” scenarios that have occurred since 1957, when unemployment was falling by an average of 10% at the time of rate decreases.

The current cycle can also be distinguished by the level of government debt and individual savings. The U.S. personal savings rate is a pitiful 2.9%, indicating that people are living beyond their means. The government’s debt-to-GDP ratio has increased to 123% concurrently. During the previously indicated periods of soft landing, the average personal savings rate was 9.2%, while the government debt-to-GDP ratio was far lower at 51%.

As a result, compared to previous cycles, the current economic scenario has stronger trends in unemployment, lower savings rates, and higher levels of government debt. These factors point to a lower chance of a soft landing and a larger chance of a recession in the near future (2024–2025).

However, the steady GDP growth and consumer expenditure are a counterbalance to this bleak picture. GDP growth in Q2 2024 was 2.6% (updated to 3.0%), a substantial increase over the average 1.2% observed in recessions that follow rate cuts. However, this rise had place in the context of low savings and a large national debt—factors that have supported expenditure.

A change in the direction of higher savings or a halt to the growth of public debt might have a significant effect on GDP and spending.

In conclusion, strong GDP and consumer spending provide some cause for optimism, but the whole context—emphasized by previous rate-cutting outcomes—indicates that these kinds of monetary policy changes by the Federal Reserve are frequently a precursor to economic contraction. The few instances in history of this pattern’s divergence required considerably better economic fundamentals than what is currently apparent.